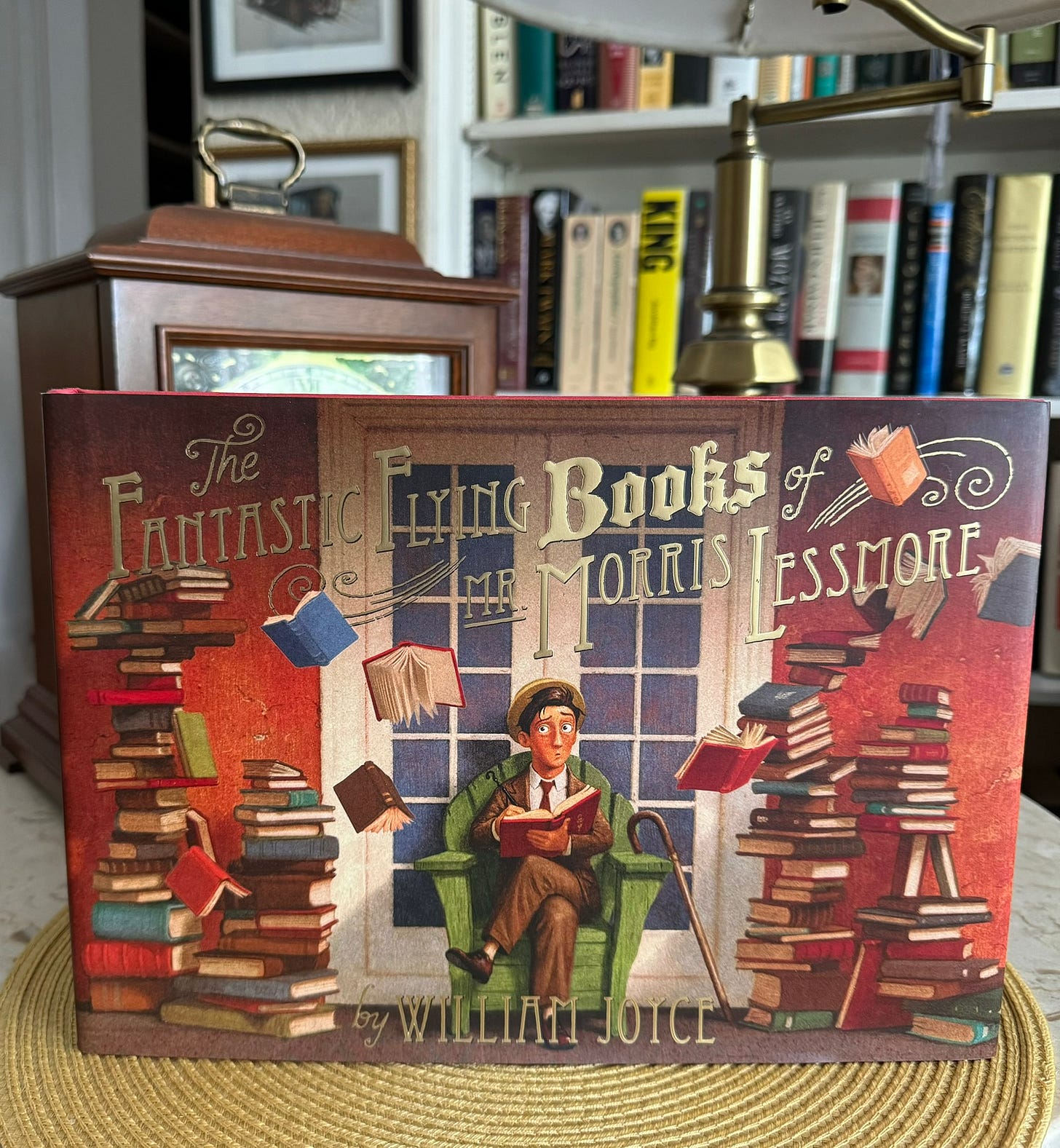

The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore

Last weekend I was gallivanting around Duluth, Minnesota, and along the North Shore, then this work week was the busiest I’ve seen all year, and the combination utterly kneecapped my reading – no point in understating it. So today we’re going to gently lean back into things with something easy and fun: the children’s book The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, written by William Joyce and illustrated by both Joyce and Joe Blluhm

I have small shelf of children’s books here in the apartment and a more generous selection in my reading apps. An odd thing, you might think, but as a friend of mine says, the best children’s books are also written for adults (they’re the ones reading these things to kids, after all). This means that while we grant them their simple stories and lessons, they shouldn’t be dumb, the art ought to be involving, and in the best cases they might have a power that’s intensified when the reader has been alive longer than a child.

Today’s case is The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore started as an animated short film in 2011 directed by William Joyce and Brandon Oldenburg and the book adaptation I have here was published in 2012, so the media form moved in the opposite direction of our now nearly universal book-to-film world. The book, we’re told, is an allegory about the power of stories, and that device gives two problems: kids, I think, aren’t likely to “get it” and allegory tends to produce some awfully lazy writing.

For now, let’s just look to the story itself.

(Morris Lessmore is a bad but euphonious name apparently inspired by William Morris; Morris died in 2003, had been vice president and director of library promotion at HarperCollins Children's Books, and was a mentor to Joyce)

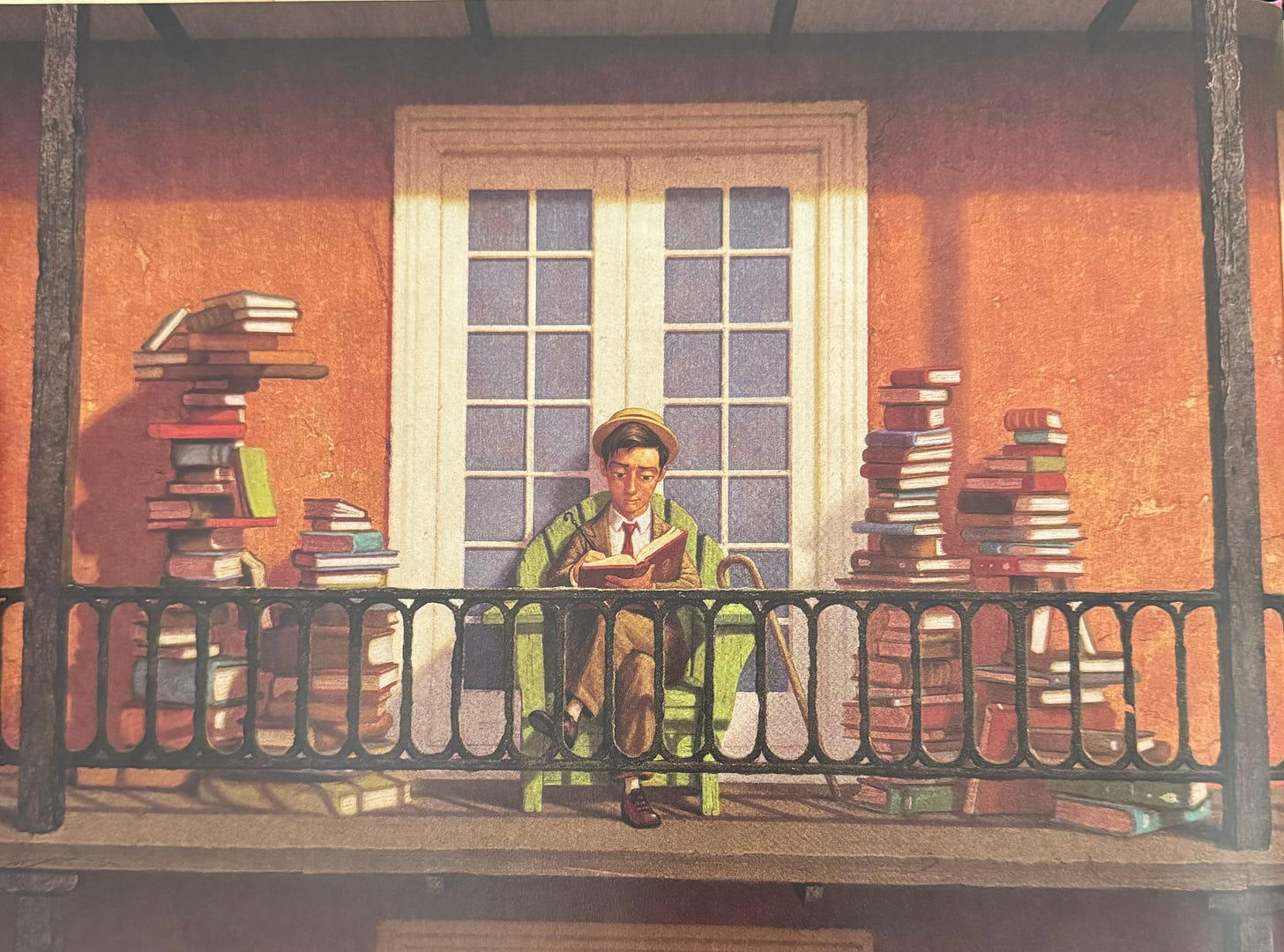

We open the book to Morris Lessmore sitting in an easy chair on his balcony, impractically surrounded by disorganized piles of books, and writing what in what I take to be his journal.

We’re told:

Morris Lessmore loved words.

He loved stories.

He loved books.

His life was a book of his own writing, one orderly page after another. He would open it every morning and write of his joys and sorrows, of all that he knew and everything he hoped for

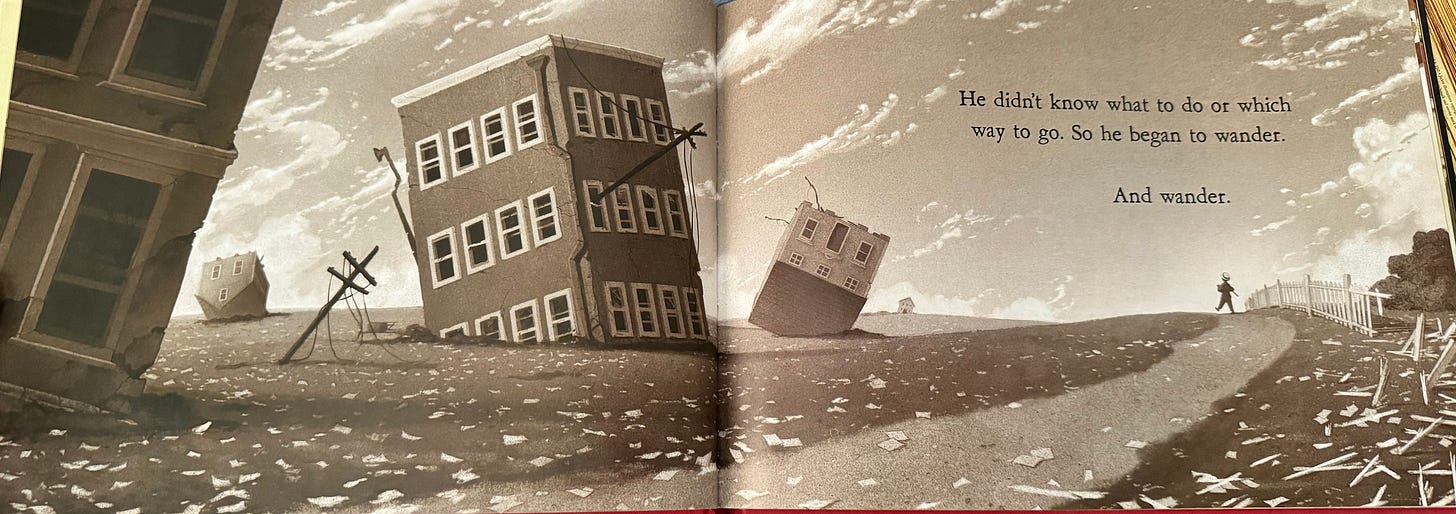

One day a storm blew in and upset everything: not only displacing him from his home but scattering “even the words of his book,” leaving him to wander in a colorless world.

It’s not clear why he’s wandering instead of rebuilding and staying with his community, the last thing you would do in this situation is ‘wander.’ But this is an allegory, so I guess the storm and his aimlessness are metaphors and don’t therefore have to ‘make sense’ - at least I suspect that would be the unfortunate defense.

(or it makes sense ‘if you really think about it’ - allegory: the literary device for stoners.)

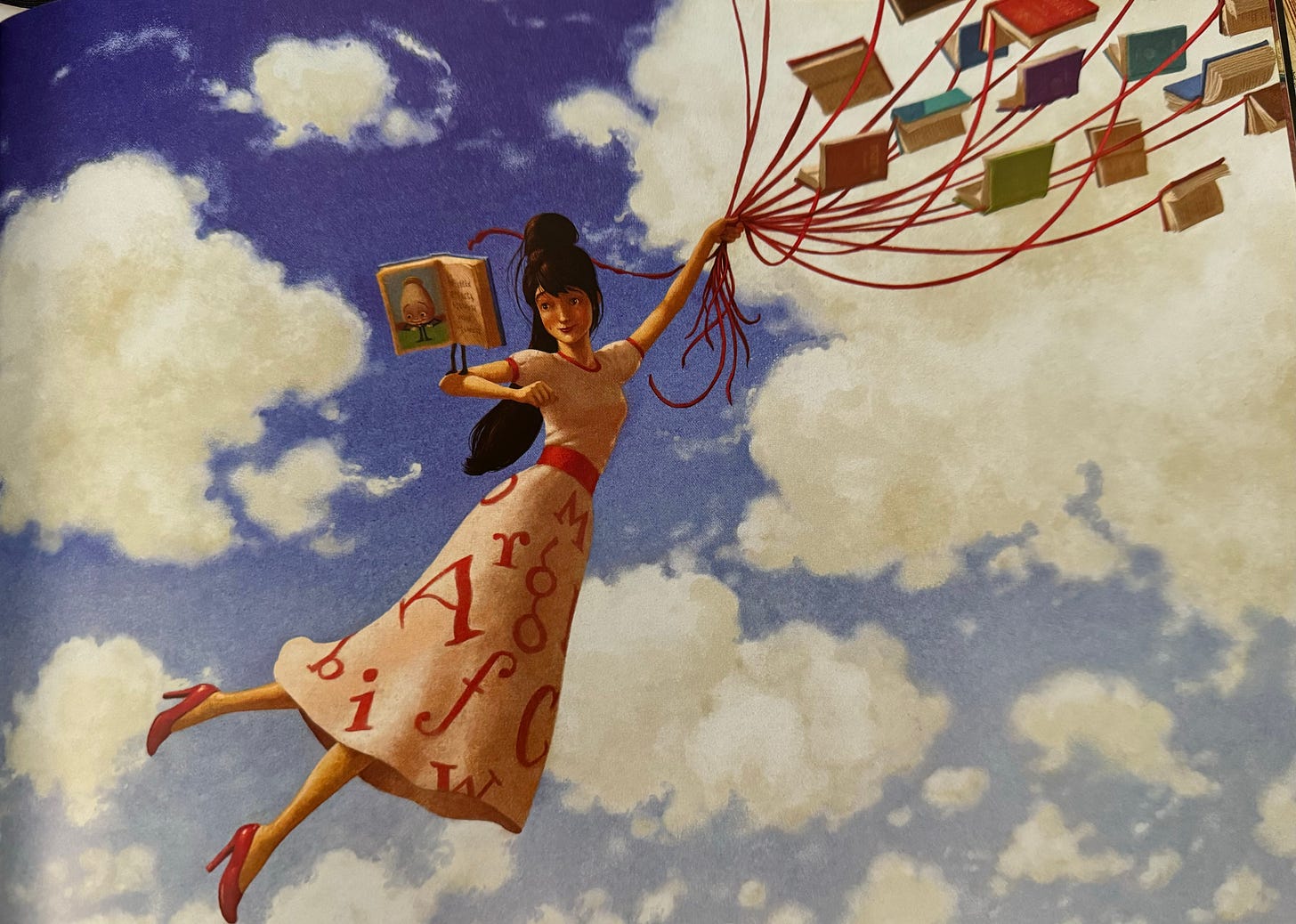

Anyway, on this pointless walk our now achromatic Morris Lessmore meets a “lovely lady,” full of color, who is guided through the sky by a “squadron” of books.

(although how lovely can she be? She isn’t even given a name)

Morris wondered if his book could fly.

But it couldn’t.

It would only fall to the ground with a depressing thud.

The flying lady knew Morris simply needed a good story so she sent him her favorite. The book was an amiable fellow, and urged Morris to follow him.

I’ll admit, this doesn’t make much sense to me. Presumably he’s colorless and his book cannot fly because things have been upset by an unexpected storm in life and now the reader is primed to see how books can get you through and turn it all around. . . but why didn’t his books fly before the storm? what makes a book fly at all? Is the implication that up to now Morris had been reading the wrong books? If so, why? we’re told at the beginning of the story that Morris loved his books. Going deeper (sorry), Morris wonders if “his book could fly,” and that book is his writings of “his joys and sorrows, of all that he knew and everything he hoped for” – so what does it mean if THAT of all books can’t fly? Is it all a matter of his attitude toward books? Do the books need to come from somewhere special to fly?

Obviously – obviously – I’m reading too much into this, but you can see how the ‘plot’ here is thin as onion skin - the story turns on nonsense or unexplained details - and this has more than a little to do with its allegorical nature.

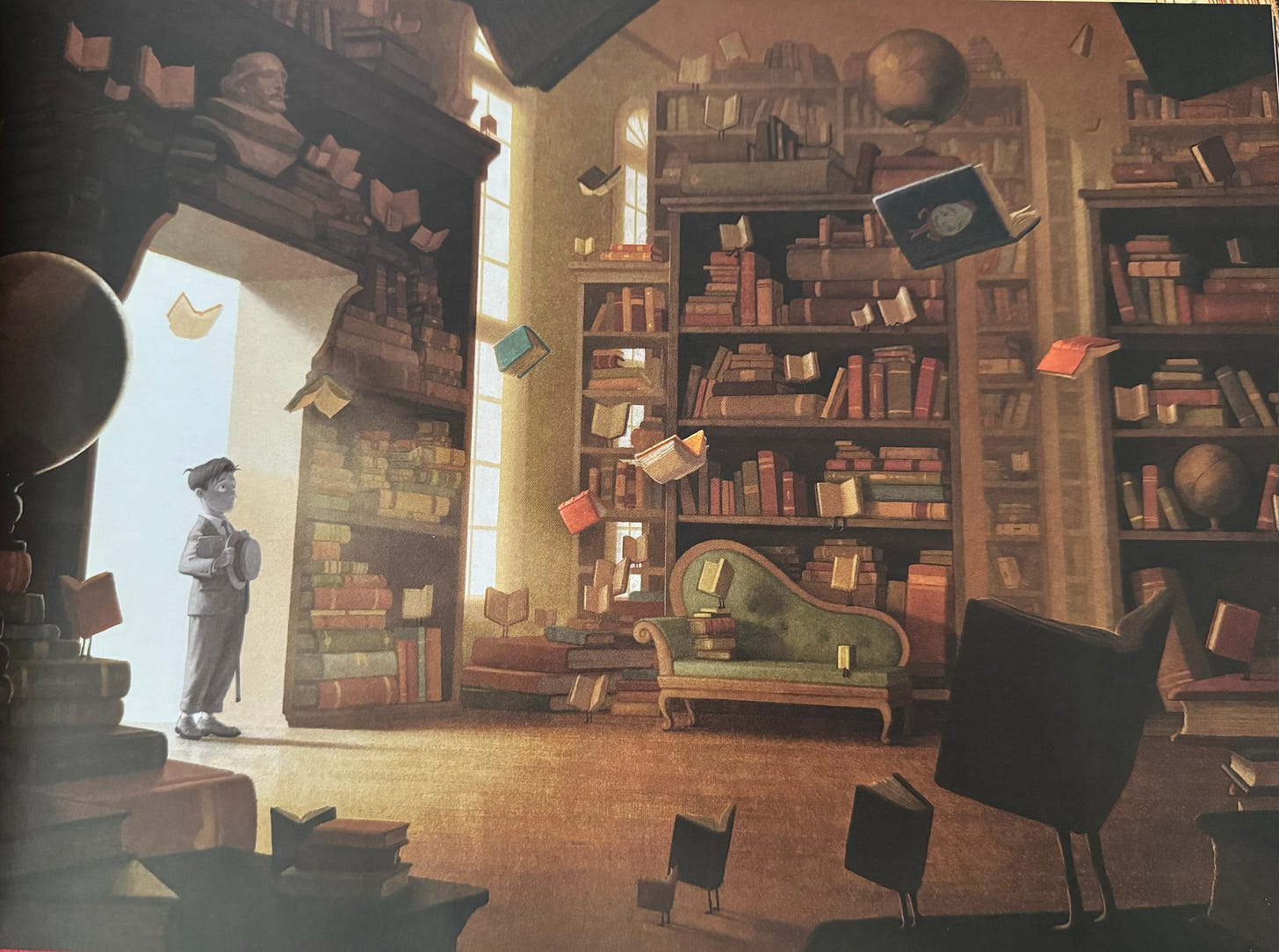

Now this anthropomorphic book the mysterious lady in the sky gave to Morris leads him to a library, he enters, and with all he discovers inside he changes back to full color:

And here Joyce gives a marvelous passage on the thrill of reading and of libraries:

Morris slowly walked inside and discovered the most mysterious and inviting room he had ever seen. It was filled with the fluttering of countless pages, and Morris could hear the faint chatter of a thousand different stories, as if each book was whispering an invitation to adventure.

A thousand different stories, each whispering an invitation to adventure - lovely. And that adventure is why those of us who read do so. Each book might be a new favorite. Each book might teach or show you something new. Each book, if you are open to it, might reshuffle your mind and therefore change you in ways you couldn’t expect.

This passage especially reminds me of a snippet of prose in C.S. Lewis’s An Experiment in Criticism:

Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realise the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors. We realise it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others.

So reading is an inherently vulnerable, thrilling, and growing adventure.

Surrounded by all this, “Morris’s life among the books began.”

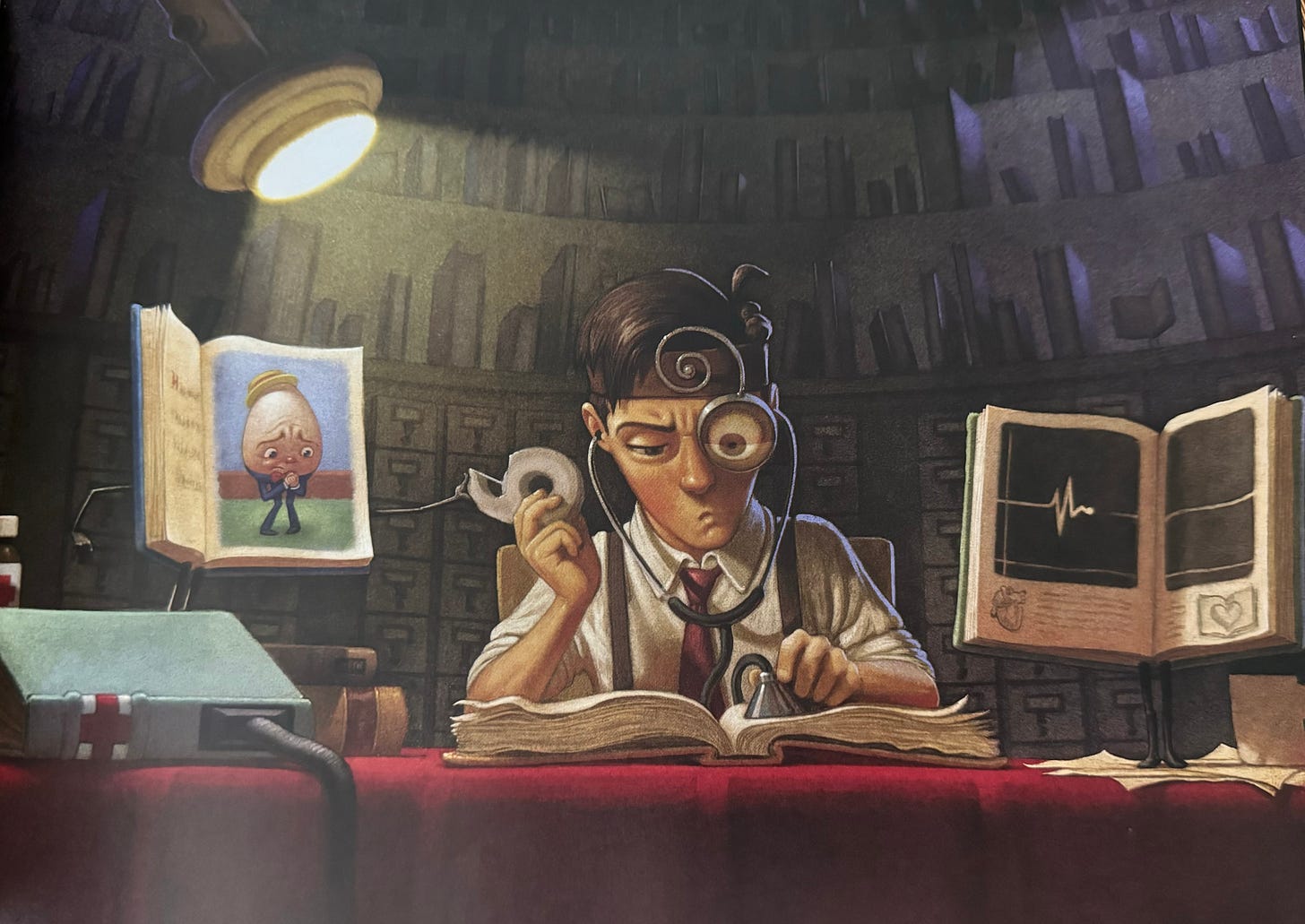

Like we all do, Morris cares for his books, gets lost in his books and might “scarcely emerge for days,” and importantly he shares these books with others.

Indeed, it’s not merely that when he entered the library his “life among the books began,” but, more to the point, he gave his life over to books.

Morris does this for months, for seasons, and for years. Each night settling in when he could then turn to his own book and write “. . .of his joys and sorrows, of all that he knew and everything that he hoped for.”

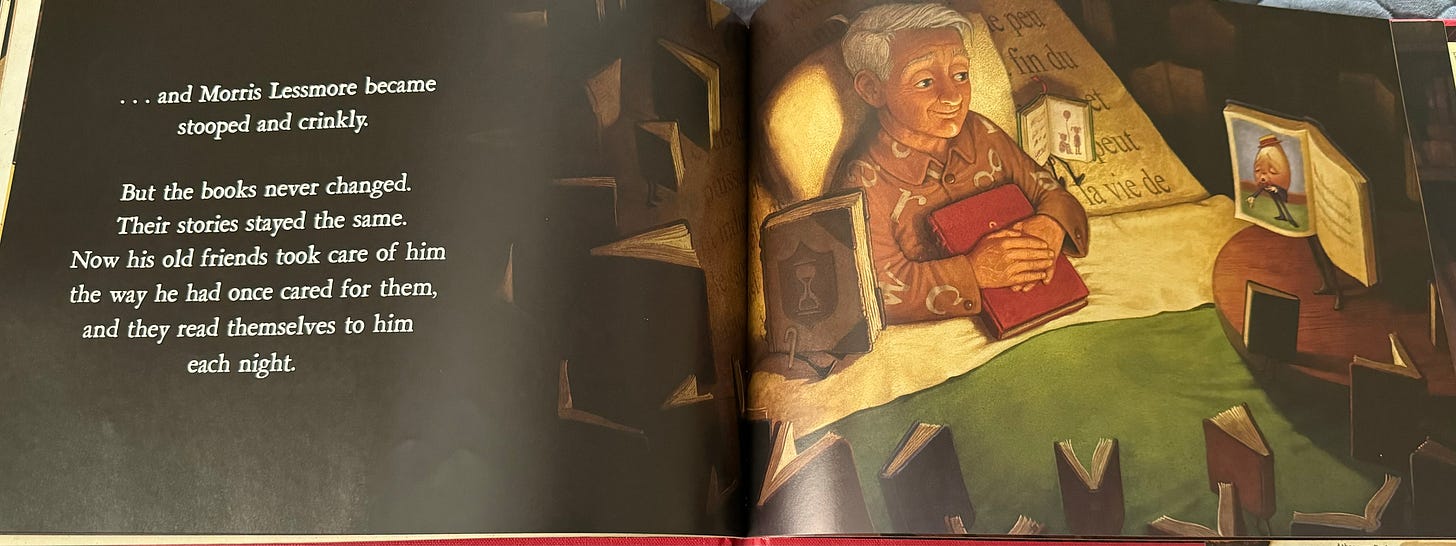

As someone who also settles in every night and journals his day, I never tire of that lovely line. And Joyce gives more at the end where we see an old, frail, but happy Morris Lessmore:

. . .and Morris Lessmore became stooped and crinkly.

But the books never changed. Their stories stayed the same. Now his old friends took care of him the way he had once cared for them, and they read themselves to him each night.

That stops me every time I read this little book. “. . .the books never changed. Their stories stayed the same. Now his old friends took care of him. . .”

People are not terribly reliable things. We change, we’re fickle, we’re mendacious, we’re any number of things, but we’re not consistent. Dogs and books are consistent. When I sit in my apartment alone and in need of quiet, I find peace in being surrounded by old friends who never change and can always be relied on, including the The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore.

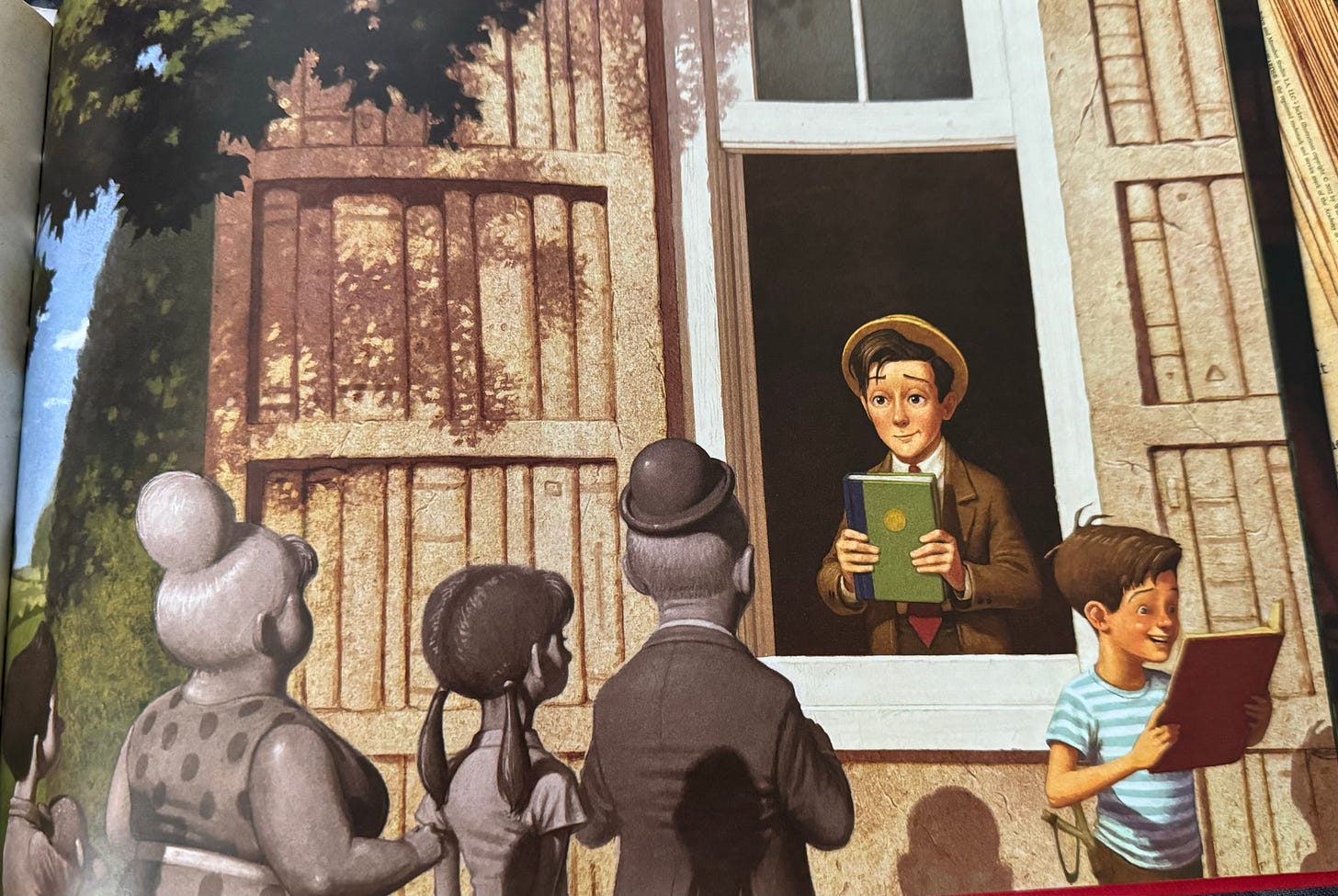

The end of this book is fanciful. One day Morris fills in the last page of his book and it’s time for him to “move on.” He flies away, young again and guided by a flock of books. All just before a little girl steps up to the doorway of the library, finds Morris Lessmore’s book, begins to read, “and so our story ends as it began. . .with the opening of the book.”

(Clearly the lady from earlier in the book had just popped her clogs, which is a little weird and makes me wonder: did she have a book of her own? She didn’t even have a name. Also, notice Morris’s book is still in the library, on the floor – so it never was able to fly.)

I’ll never know when I’ve filled in the last page of my journal. We don’t get the luxury of knowingly easing up out of our comfy reading chair in a guaranteed old age and ‘moving on.’ But as a poignant ending to a flawed book with several wonderful moments that I treasure when I need them, I’ll take it.