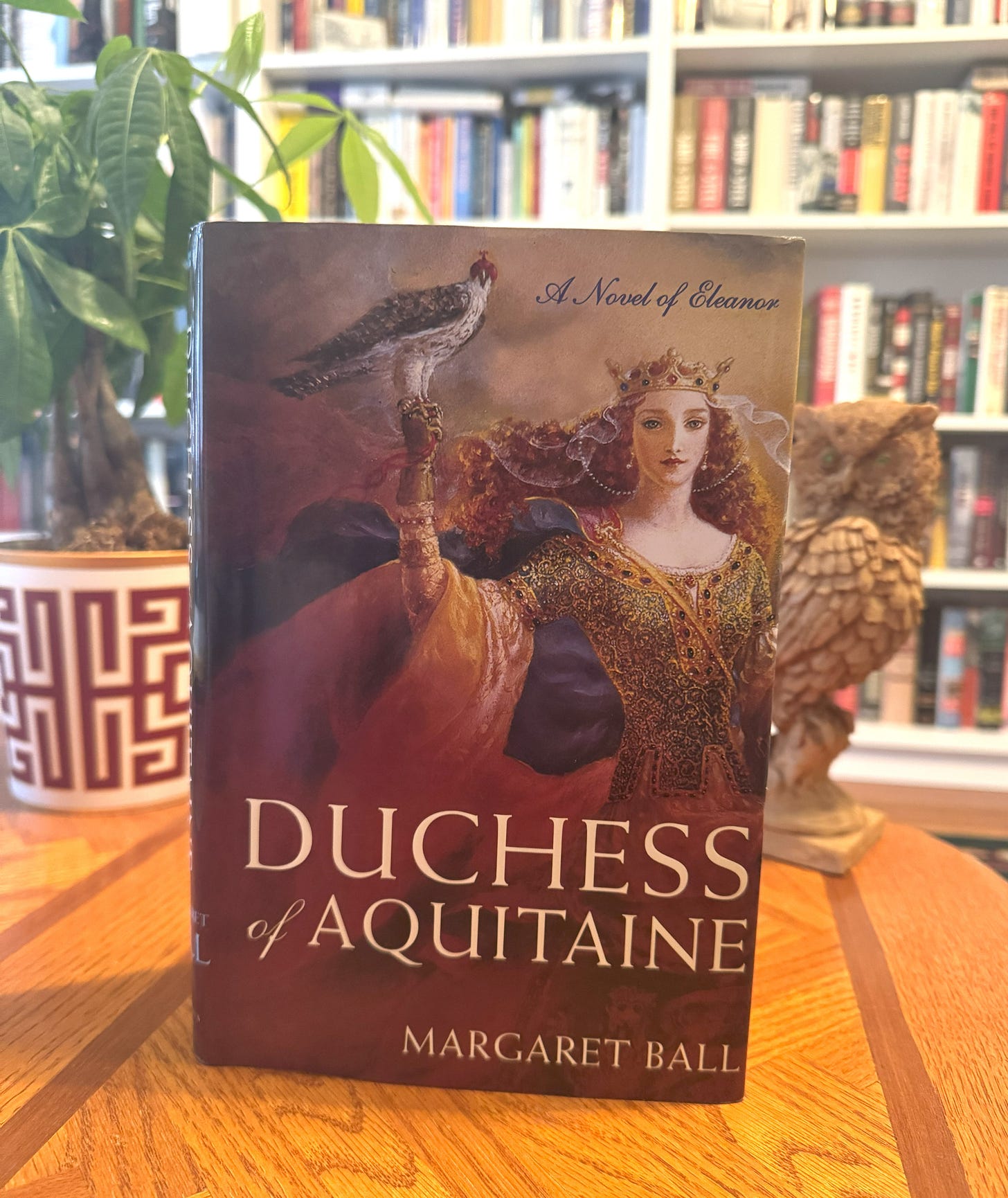

Duchess of Aquitaine: A Novel of Eleanor by Margaret Ball

Last week I read Margaret Ball’s 2006 historical novel Duchess of Aquitaine: A Novel of Eleanor. Eleanor being Eleanor of Aquitaine whose biography practically begs for dramatization. As Dina Portway Dobson writes:

Great in her ancestry, great in her life, and great in her descendants, it is not easy to tell the story of Queen Eleanor in short space. Her life lasted for eighty years, and for all but the first fourteen she was a queen. As the chronicler expressed it, “wife of two kings, and mother of three,” circumstances gave her the opportunity for playing a great part in politics, and her vigorous character made the most of it.

“lasted for eighty years,” but in this novel we are only given the young Eleanor, from the time of her father’s death, through her marriage to Louis VII of France, and just to her marriage with Henry Plantagenet.

It is difficult not to compare Ball’s Eleanor with, for example, James Goldman’s characterization in his play “The Lion in Winter,” in which we are given an older, more cynical, towering, and completely brilliant Eleanor – she seems nearly physically returned to her and Louis’ crusade in the Holy Land when she says:

I even made poor Louis take me on Crusade. How's that for blasphemy? I dressed my maids as Amazons and rode bare-breasted half way to Damascus. Louis had a seizure and I damn near died of sun burn but the troops were dazzled.

While the marriage between Eleanor and Louis would deteriorate on this, the Second Crusade, and it had many unhappy times, earlier on their road (than told above by a later Eleanor) we are given a wonderful three-dimensional portrait of her travel:

In the first days of the march south along the coast, Eleanor loved it all: the morning and evening smoke of the campfires, the cold clean winds off the mountains, the icy streams they washed in, the slow unfolding of new hills and forests. . .She felt as if she were reborn and riding into a world made new with promise. The leaves on the trees were filled with green light, the droplets of water that clung to their edges and that sprinkled the riders were like a continual light baptism in water more holy than any stale basinful in a church font. Belle-Belle, the pretty white palfrey that Amicie de Périgné had brought for her in Hungary, tossed her head and almost danced along the narrow path. A lucky chance, that, having her master of horse join the Crusade; she had not been so well mounted since she went to Paris. The earth beneath her palfrey’s feet and the trees rising above their heads were her cathedral, the graceful arch of the branches more lovely than anything little Abbot Sugar could cause to be made in stone, the mosaic of green leaves and pale blue sky finer than any window of stained- and leaded-glass pieces.

It is with this atmospheric and aesthetic - even graceful - writing that Ball gives life to a believable world of believable characters; characters who, sure, radiate in their status, but also get sweaty and dusty (they smell), need to bathe, tire, bleed, and so on.

Their memorable and alive personalities, different from each other and changing internally through the story, help to both smoothly move the plot along and invest the reader. You come to hate Louis, almost wanting to reach into the pages and strangle the miserable prick yourself; You cannot forget Geoffrey of Anjou (Henry’s father) even when he’s off scene; Eleanor’s sister is smaller but her own present self, despite typically being used to remind the reader about Eleanor’s distinctive and difficult station; and our impression of Henry alters in a way that’s remarkable given how little he’s seen in the book.

Still, Eleanor is obviously the heart of the book. And while she is young here, and while she learns and matures as our story and characters age, there is still something more in her, even in the first chapters:

“No.” Somehow the girl [Eleanor] stood a few inches taller, and the reverend archbishop of Bordeaux stopped in midsentence. Arnulf waited, eager in spite of himself to hear what had inspired this young girl to burst in and interrupt men at important business.

In the breath before she spoke again, he realized that all three of them were waiting on her words. How had she managed that? Instead of being turned politely around and told to go finish her needlework, she was commanding them all. When she spoke, he could almost see the letters forming over her head, illuminated in gold leaf and vermilion, stamped with the ducal seal of Aquitaine.

This is mirrored in the final third of the book in a scene demonstrating the same intellect and command through force of personality found in the above, but also demonstrates a markedly increased confidence in herself:

“We had best discuss exactly how to present the plan,” she said. I need to know more. . .much, much more. . .about the lines of power and inheritance in these kingdoms, so that I do not make any mistakes with Louis. Our people I know, but if we want to make sur that this plan succeeds, I need to also know who will support it and who will lose from it here in Outremer.” She glanced at the men gathered around the table, all three waiting on her word, her decision. “I want to know who holds each fief in Outremer, whom he holds it from, where his loyalties lie and where his debts are, whether he gained his lands by conquest or inheritance or. . .a fortunate marriage!” She deliberately slowed and accented the last words and laughed up at her kinsman. . .and was pleased to see a look of surprise in his eyes.

I find the sureness in knowing exactly what information to collate and punctuating it with a bit of sardonic humor, all contrasted with the earlier scene, to make this a brilliant small moment.

Such is the strength of this novel that you almost believe Eleanor at the end, despite knowing her future, when she says:

And best of all, he was young enough to accept her guidance. She would teach him to rule by day, and together they would learn the arts of love by night, and together they would make an empire over half the world – yes, and many sons. All that was promised her by the vision in the fountain would be true now, even the crown; it was only that she had not interpreted it rightly the first time, had not chosen the right crown.

“this time,” she said to herself, “I am doing everything right.”

It is nearly 2025 and Margaret Ball has not written a second book, giving us the tribulations of Eleanor’s later life, which would have been welcome. Still, her choices of minimizing Henry’s presence and then ending the book with their coming together works on its own. Duchess of Aquitaine is a thoroughly satisfying and knowing book that I would recommend should you stumble on a copy.